Home > Museum Report > VOL.14 > Display Design Enhances the Beauty of Japanese Art

The years since I joined the Tokyo National Museum in 1999 have seen a succession of major events for the museum, including the opening of the Heiseikan (Japanese Archaeology Building), the museum's becoming an independent administrative institution, and the renovation of the Honkan (Japanese Gallery). In particular, the Honkan renovation in 2004 completely renewed the exhibition system, bringing together displays by subject on the first floor and making the second floor an exhibition of Japanese art through the ages with displays arranged chronologically. Displays by genre are meaningful both for people who want to view them in depth and for specialists. They are too specialized, however, for visitors from overseas and for the general public, and do not offer them an overall grasp of what Japanese art consists of. For this reason, we categorized the artwork according to period, and used the entire gallery to display them in conjunction with their historical and cultural background. A major factor in implementing this chronologically arranged exhibition was the large-scale organizational transformation that took place when the museum became an independent administrative institution in 2001. Prior to that, the organization was set up entirely according to genre, with paintings, crafts, and so on managed completely separately, partly for reasons of artwork management. That meant that people researching paintings were unable to enter the crafts storerooms, and vice versa. This would not make the museum an enjoyable place for visitors, however, so the specialized sections were abolished, and the Curatorial Board also disappeared. This was a great shock for the curators, but the present shape of the museum was arrived at with an awareness that it is the job of museum curators to think not only about their own specialized subjects, but the museum as a whole.

Preparation of chronological exhibition imposes a lot of work on the curators. For example, when displaying tea-ceremony utensils, they might well think that this scroll goes with this tea bowl and that kettle. A display of tea-ceremony utensils cannot be completed without the cooperation of people in many other fields, such as paintings, metalwork, and ceramics. Furthermore, Japanese art cannot be exhibited year-round for conservation reasons (items such as paintings and calligraphy can only be displayed for four weeks out of a year), which means that complicated coordination of exhibitions in accordance with the Museum's yearly schedule is required. This sort of thing is difficult for people who are not insiders. Herein lies the significance of designers working within museums, who can devise display methods as required. Coordinating between the different genres and producing a yearly schedule means we can effectively attract fans of Japanese fine art by letting them know when they can view famous works such as Hokusai's "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji," for example, which should increase the number of repeat visitors.

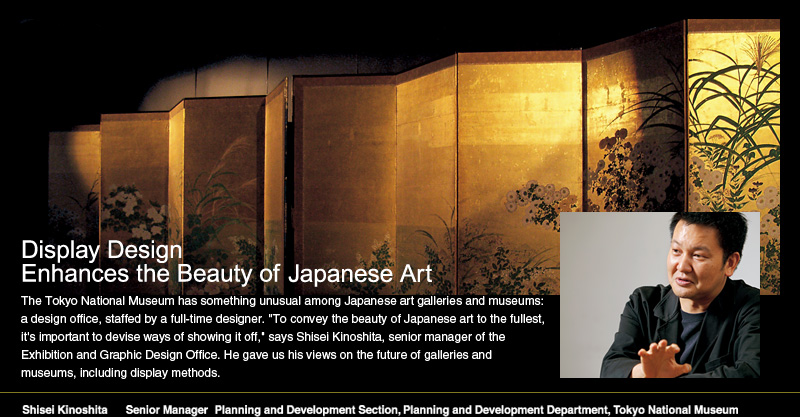

Lighting experiments: changes in the expression of painted autumn grasses.

(a) Flat light

(b) Right-left balance changed.

(c) Warm lighting like evening light.

(d) If the lighting is dimmed further, the gold leaf ground stands out.

"Autumn Grasses" folding screen by Tawaraya Sousetsu (Edo Period) in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. (Important Cultural Asset)

I feel that a major factor in bringing out the beauty of Japanese art is the use of lighting. It's fine just to train a spotlight on the Venus de Milo from above, for example, but unless you try illuminating Japanese Buddha images from above and below or from a variety of angles in a process of trial and error, their original expression will never emerge.

In last year's special exhibition from the Price Collection, "Jakuchu and the Age of Imagination," the collector, Joe Price, had his own opinions, and we put together the exhibition using exposed displays and varying levels of lighting. This was quite adventurous from the museum's perspective, where the received wisdom is to enclose works in glass cases and illuminate them uniformly to aid visibility. We discovered, as a result, that bright illumination alone cannot fully bring out the beauty of Japanese art. For example, the dimmer the illumination of gold leaf, the more the gold glows so that it stands out almost dazzlingly. Artists in those days must have calculated the conditions under which their works would be viewed and adapted their materials and methods accordingly. This means that these works would reveal their full beauty inside a traditional Japanese house or under naturally shifting light. How far can we elicit this impact inside a museum, under artificial lighting? In this exhibition, we incorporated stage lighting techniques into the exhibition, and repeatedly experimented with different lights. As a result, we were able to produce lighting that also satisfied Mr. Price, and young visitors were overheard saying, "I never knew folding screens were so magnificent." I would like to incorporate the success of this and other special exhibitions into our regular exhibitions. This may sound rather abstract, but I feel it would make museums more interesting if, rather than simply imitating natural light or just recreating the era in which the work was produced, we can use technology to reinforce the power and impact inherent in the works.

With the Jakuchu boom and other trends, Japanese art has begun to be viewed in a new light in recent years. The Suntory Museum that opened in Tokyo Midtown this spring also focuses on Japanese art. I saw the floor plans once during the design stage, but when I actually visited I was surprised at how much better (that is, more beautifully) than I had imagined the works could be seen. As a professional, I always notice more about the lighting and display cases than the works themselves in the gallery, but at the Suntory Museum the artwork was the first thing to catch my eye. Any display that makes visitors feel that way is a good display. I myself discovered that Edo kiriko (cut glass) is lovelier than I had always thought. Japanese works of art are fragile, and must therefore be kept in display cases. At the Suntory Museum, however, they have done their best to prevent the presence of the display cases from being noticeable. I think this could not have been achieved without the case manufacturers also having a firm idea of how display cases should be made.

When the present Honkan of the Tokyo National Museum was rebuilt in 1938 (the former Honkan had been destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923; the present building was completed in 1937 and opened the following year), the mere fact that works were placed in glass cases was groundbreaking in itself. People of the time who saw it must have perceived this as a stylish museum, with its paintings behind glass. The trend spread to galleries and museums nationwide, and has become today's standard. Now, however, the trend is toward making cases as unobtrusive as possible, creating a sense of realism for the "real thing." I felt that the Suntory Museum showed me this in concrete form. This is how far galleries and museums that simultaneously protect and show off their works in glass cases have come. Of course, the fact that this museum was newly built probably enabled the management to adopt all the techniques it wanted to, but if such displays could be seen in more places I think Japanese art would become more enjoyable.

Shisei Kinoshita

Senior Manager Planning and Development Section, Planning and Development Department, Tokyo National Museum

Shisei Kinoshita was born in 1965. After completing graduate studies in the Faculty of Fine Art at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, he became an assistant in the university's Design Department and then worked for Lighting Planners Associates before taking up his present position as senior manager of the Exhibition and Graphic Design Office at the Tokyo National Museum. He also lectures in the Design Department at Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music and the Department of Crafts at Joshibi University of Art and Design. Exhibitions he has worked on include "Visions of the Pure Land: Treasures of Byodoin Temple" (2000). The Japanese Society for the Science of Design awarded him its 2006 Annual Product Award for his Renewal of the Tokyo National Museum Honkan Japanese Gallery (2004). Publications include Hakubutsukan ni Ikou ("Let's Go to the Museum") (Iwanami Shoten) and co-authorship of Showa Shoki no Hakubutsukan Kenchiku ("Museum Architecture in the Early Showa Period) (Tokai University Press).